May 31, 2012

May 25, 2012

The Dangers of Exploits and Zero-Days, and Their Prevention.

You don’t need to hear it from me that the Internet is a really interesting phenomenon, and mega-useful for all those who use it. But at the same time its openness and uncontrollability mean that a ton of unpleasantness can also await users – not only on dubious porno/warez sites, but also completely legitimate, goody-two-shoes, butter- wouldn’t-melt-in-mouth sites. And for several years already the Internet has been a firm fixture on the list of the main sources of cyber-infections: according to our figures, in 2012 33% of users have at least once been attacked via the web.

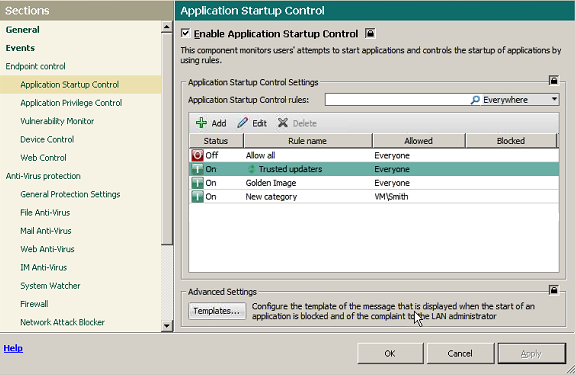

If you dig deeper into the structure of net-based unpleasantness, you always come across three principle categories of threats: Trojans, exploits, and malicious tools. According to data from our cloud-based KSN (video, details), the break-down is as follows:

The ten-percenter in the above pie chart as you can see belongs to so-called exploits (their share will actually be greater in reality, since a lot of Trojans have a weakness for exploiting… exploits). Exploits are mostly exotic peculiarities to non-professionals – while a real headache for security specialists. Those of you more in the latter category than the former can go straight here. For the rest of you – a micro-lesson in exploits…

May 2, 2012

In Updates We Trust.

Remember my recent post on Application Control?

Well, after its publication I was flooded with all sorts of e-mails with comments thereon. Of particular interest were several cynical messages claiming something like, “The application control idea is sooo simple, there’s no need for any highfalutin special “Application Control” feature. It can be dealt with on-the-fly as applications are installed and updated.”

Yeah, right. The devil’s always in the details, my cynical friends! Try it on the fly – and you’ll only fail. To get application control done properly – with by far the best results – you need three things besides that “it’s easy” attitude: lots of time, lots of resources, and lots of work going into implementation of a practical solution. Let me show you why they’re needed…

On the surface, it’s true, it could seem Application Control was a cakewalk to develop. We create a domain, populate it with users, establish a policy of limited access to programs, create an MD5 database of trusted/forbidden applications, and that appears to be it. But “appears” here is exactly the right word: the first time some software updates itself (and ooohhh how software today loves to update itself often – you noticed?) the sysadmin has to write the database all over again! And only when that’s completed will the updated programs work. Can you imagine the number of angry calls and e-mails in the meantime? The number of irate bosses? And so it would continue, with every update into the future…

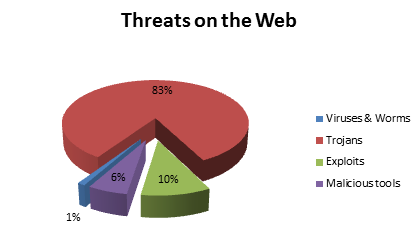

To the rescue here comes running a mostly unnoticeable but mega-useful feature of our Application Control – the Trusted Updater. It not only (1) automatically updates installed programs while simultaneously bringing the database of trusted software up to date, it also (2) keeps track of inheritances of “powers of attorney” attracted to the updating process. The former is fairly straightforward and clear, I think. The second… let me explain it a bit.

Let’s take an example. While performing an update, some software launches, let’s say, a browser (for example in order to show the user’s agreement), and transfers to it its access rights. But what happens when the update is completed? Are you twigging what I’m getting at here?… Yes – in some products the browser keeps the inherited rights until it’s restarted! So until then it could perform an action that is actually forbidden according to the security policy – for example, to download something from the Internet, and, more importantly – to run it. What’s more, the browser gets the ability to call on other programs and give them the enhanced rights of the updater. Oht-Oh!

Turns out a single update could bring down the whole security system through incorrect access rights’ management during the update process. Scariest of all is that this isn’t a bug, it’s a feature!

Anyway, back to our Trusted Updater. What it does is take full control over the update: as soon as the process has finished, it restores the rights back to what they were before the update – for the whole chain of affected programs. Another handy trick is its knowing beforehand which updaters can be trusted – there’s a special category for them in our Whitelist database. And should a sysadmin want to, he or she can add other updaters to this category with minimal effort but with a good addition to the level of the network’s overall protection from all sorts of sly backdoors.

More: The four scenarios of implementing for controlling software updates…

April 16, 2012

Apple – Listen to Us, Before It’s Too Late!

Which is better – Mac or PC?

By now the eternal debate will have come on to the radars of even the most non-geeky types, and those who still don’t have a position on it – normally a passionate and unwavering one – are fast becoming extinct. Last week of course the ongoing debate was seriously influenced by news of the Flashfake botnet for Mac OS X. It seems that cybercriminals are now joining the large numbers of users migrating from PC to Mac…

April 2, 2012

The World’s Gone Virtual – So Have We.

Why and How We Decided to Protect the Virtual Environment.

Over the last dozen years in the IT industry all sorts has gone on, but in the main what happened was the blowing up, bursting, and blowing up again of bubbles. Thankfully, against this depressing backdrop there are several examples of how things should be done – stories of technologies passing through all the stages from conception to industrial mainstream. One of the most interesting examples of this is virtualization.

To start, as per tradition in these tech-themed posts, let me go over the basics. For those who already know the basics of the topic, you can skip this by clicking here.

More: Agent-less malware protection vs Disadvantages of virtualization security…

March 17, 2012

Cassandra Complex… Not for Much Longer.

Top o’ the day to ye!

It’s fair to say I’m a bit of an IT-paranoiac, and most of you will know by now I’m not one to hold my tongue about my fears of possible future Internet catastrophes, or the greed and degeneracy of cyber-wretches – plus the massive size of the threat they represent – and so on.

Because of this tendency for speaking openly and plainly I constantly get accused of purposefully frightening everyone (and in my own self-interest). But I don’t mind, even though it’s nonsense. So I’ll keep on calling a spade a spade – telling people what I think is right – regardless!

The evolution of cyber-Armageddon is moving in the predicted trajectory (proof it’s not just a matter of my frightening folk just for the sake of it); this is the bad news. The good news is that the big-wigs have at last begun to understand – to the extent that often in discussions on this topic are heard my horror stories of old practically word-for-word. Looks like the Cassandra metaphor I’ve been battling for more than a decade is losing its mojo – people are listening to the warnings, not dismissing and/or disbelieving them.

March 16, 2012

Wham, Spam, Thank You Ma’am: The Quick Rise and Fall of Image Spam.

Here it is, the original Spam! Hmmm, yummy… but healthy? Is anything in a tin? Ok, will leave off the foodie lecturing just for today…

// It’ll be interesting to see if this post with the above pic in it will get through the anti-spam filters of those who subscribe to my mail-outs.

So here we are once again on a subject that it seems will never go away – spam, this time about a particular kind thereof – “image spam” – and the protective technologies that fight it.

I’ll start with a brief bit of historical background.

March 7, 2012

Emulation: A Headache to Develop – But Oh-So Worth It.

What’s an ideal antivirus? Something that would feature the following:

- 100% protection from malware;

- 0% false positives;

- 0% load on system resources;

- No questions asked of the user; and

- Lasts forever and is for free!

Like anything ideal though, this is of course a fantasy – quite unattainable in real life. But it’s nevertheless still worthwhile contemplating since it provides a fixed reference point for security developers: every company can then try to get as close to the ideal as it can within the limits of its financial and professional resources.

More: An important but unheard instrument to combat unknown threats …

February 27, 2012

Halt! Who Goes There? Or Remedy #3.

Security people, sysadmins and, generally, all those who by virtue of their employment take loving care of corporate networks – all these people have plenty of headaches. Indeed, a veritable cornucopia of headaches. And, of course, the main source of trouble is… you guessed it, users. Tens, hundreds, even thousands of users (depending on your good fortune) who have problems 24/7. As for us, we try to help these ‘frontline soldiers’ get to grips with their headaches, using the full extent of our resources in our field of competence. Below, we discuss one very helpful remedy that fits this combat strategy to perfection.

There are, in fact, three separate remedies. But they all tackle one problem – keeping users under control. And there are helpful side effects – enforcing a centralized IT security policy, fool-proofing, and automating the ‘donkey work’. That’s right, I’m talking of three new features included in the new version of our corporate solution, Endpoint Security 8: application control, device control and web control. This post is about application control (or simply AC without the DC).

Most of the time it’s a struggle to keep computers clean. Users are given to downloading questionable “cool warez”, installing them, trying them out and forgetting all about them. As a result, in half a year the computer normally turns into an unmanageable software zoo, becoming unbelievably error-prone and slow. And, of course, the abovementioned “cool warez” can easily be virus-ridden, pirated, or at best counterproductive.

There are different ways of getting out of this predicament. Some companies wag their finger at users and strictly forbid them to install software on their computers (without actually enforcing a ban). Others simply make installing software impossible in one way or another. AC is, in fact, an elegant compromise between the two.

February 23, 2012

Features You’d Normally Never Hear About – Part Four.

Hi all,

Once again, the subject is spam.

Depending on the “stars” and the time of year, the proportion of spam can range from anywhere between 70 and 90% of all email traffic.

Sounds like a lot, eh? But when you take all Internet traffic into consideration, it’s not actually that much – email traffic accounts for around just 1%. On the other hand, you can’t just forget about spam. Here is a bit more about spam’s role in the cybercrime ecosystem. Combating this particular evil is part of the massive war we are waging on cybercriminals. It’s no exaggeration to say that if we fail on this front, the rest of our efforts will amount to nothing.

In other words, we love anti-spam technologies and promote them as much as possible. There is, however, a subtle difference from anti-malware technologies. More precisely, there are different criteria for evaluating the quality of protection for anti-spam and anti-malware technologies. For malware it’s fairly easy: the higher the detection level, the better. For spam it’s more important to have no false positives. This is quite reasonable: it’s much better for the user to take a couple of seconds to delete a spam message that sneaks through the filter than miss important business correspondence. So, protection against spam is, in a way, a more complicated task, literally trying to kill two birds with one stone. In this difficult task, cloud technologies are a great help.

As I wrote earlier, we’ve been using cloud technologies for a while, and with considerable success. But one interesting detail has amazingly been overlooked, and unfairly so. In the cloud-based Kaspersky Security Network (KSN), (video, details) there’s a rather impressive anti-spam cloud. It started from the Urgent Detection System (UDS). The link to similar anti-malware technology is no coincidence: both are based on similar principles.

This is how the traditional anti-spam technology works.

Let’s say an email arrives at a computer. It is immediately assailed by various anti-spam technologies, both local and cloud-based, which test the message and give verdicts. Based on these, the system decides whether this message lives or dies.

And this is what happens in the UDS.

The system takes a micro-signature from the email message and sends it to the cloud to check it against a dedicated spam database. Earlier we used 16-byte hashes; in 2011 we started the UDS2 (UDS 2nd generation) procedure involving 4-byte fuzzy hashes, which are more effective against obfuscated texts and are therefore better at filtering out spam. Importantly, these hashes do not create extra work for the analyst, since the system creates them automatically based on collected spam samples.