November 19, 2025

Easter Island: the main whats, hows, whens & whys…

After finally getting to Easter Island (in two senses of the word “finally”) – let’s get going around this fascinating island…

I left off last time with our arriving at Mataveri International Airport (IATA code: IPC). The airport itself is nothing remarkable, so I’ll skip ahead: what’s there to see, how many days you should spend here, and what you should pack and wear. And of course, the eternal questions: how did people even get here way back when – and why did they carve these famous stone statues? ->

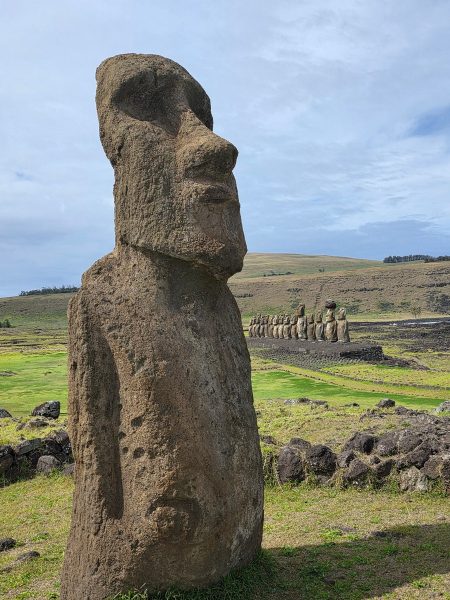

What to see: Of course, the statues themselves – several hundred of them all around the island either standing or lying down – plus the quarry where they were carved. There’s also the stunning volcanic coastline to walk along, the climb up the Rano Kau caldera and the hike around its rim, volcanic caves, and a few other attractions.

How many days to spend on the island: If you’re in a rush, you could technically see the main sites in a single day. Just rent a car or hire a minivan and driver, and race around snapping photos and ticking boxes. But honestly, I wouldn’t recommend that. The first day will mostly go to recovering from a long and exhausting flight, and on the second day you can explore the main highlights at a relaxed pace. By the third day, you’ll really start to feel the spirit of the place – meditating on endless ocean views with the stone statues in the foreground, and that’s when the island truly makes an impression. That’s the real joy of being here. So, my minimum recommendation is three days. You could easily stay longer – there are hiking and biking trails that crisscross the whole island – so for a thorough look, five days is ideal; however, three days is plenty for full immersion.

What to wear: Given the tropical climate, it’s always around 20–25°C here. However, it’s really windy!…

And since you’re basically always near the shore, you’ll want a windproof jacket.

Most of the time though, a t-shirt and shorts will do.

Footwear is important! You’ll spend a lot of time walking over volcanic rock, so trekking shoes or sturdy sneakers are highly recommended. Hiking boots are overkill, and it’d be a shame to ruin your more lightweight running shoes. Aim for something in-between.

And don’t forget a hat, sunglasses, and swimwear – after all, there’s a beach here! That shouldn’t come as much of a surprise; however, unfortunately, most of the coastline features zero beach – instead there’s just craggy black volcanic rock. There’s just the one sandy beach ->

Don’t get your hopes up about the ocean’s temperature – it’s cold since we’re in the South Pacific where the currents bring water from the Antarctic.

Right next to the beach you’ll find several moai statues:

Everything here’s well protected: the statues are fenced off and cared for as they should be:

The other moai around the island are looked after, too ->

But before I take you on a virtual tour of some of the main sights, let me briefly tell you about the island’s geography and geology…

First thing’s first: the island is small and triangular – about 16 by 17 by 24km – with a circumference of roughly 60km (here it is on Google Maps) ->

Easter Island is volcanic in origin – having formed as a result of a “hotspot” breaking through the Nazca oceanic tectonic plate. These upwellings of magma created chains of volcanoes, some of which never reached the surface, while a few did and became islands. You can see this chain on the map:

In other words, the island is entirely volcanic: it’s dotted with small volcanoes (actually just the summits of two-kilometer-tall underwater mountains), and the shore, as mentioned, is mostly made up of black volcanic cliffs.

According to geological research, the base of Easter Island began to form around 2.5 million years ago, while the peaks of the volcanoes are only a few hundred thousand years old – with the latest eruption occurring around two thousand years ago (so, during the Roman Empire). That makes it a geologically “young” island, which seems obvious from the barren, volcanic terrain along its shores:

Still, to me it hardly looks like two millennia have passed: the volcanic rock isn’t as eroded as what I normally see around the world. But then again, I’m no volcanologist or oceanographer…

In Kamchatka, Indonesia, and Hawaii, similar lava fields became overgrown with scrub or jungle in ~2000 years. Here though, for some reason, the rocks remain exposed. I find it hard to believe it’s because of human intervention.

Let’s leave aside the formation of underwater volcanic chains, which occasionally give us beautiful places like the Kurils, the Galápagos, Hawaii, the Maldives, and so on. Instead, let’s return to the historical question: How did people end up on Easter Island – so far as it is from anywhere? These people lived here for centuries, founded the most remote civilization on earth, and carved and installed these here massive moai statues.

So, how did they get here – and where from? There are many theories, but genetics and archaeology seem to have the answer. And it goes way back – even to before the time mammals finally shook off the dinosaurs and began ruling the world. But if we dive into those prehistoric details, we’d never emerge again. So, let’s skip all that and bring the history lesson to more modern times.

Homo sapiens began settling across Oceania around 3000–4000 years ago. At first, they could walk over land (as sea levels were lower), but as time passed, they began to cross small stretches of water. Eventually, these persistent folks learned to build boats and venture out into the open seas. They settled in vast swathes of land, but always wanted to go further. Step by step, the early Oceanic navigators ventured farther into the unknown. The lucky ones found uninhabited atolls, archipelagos, and isolated islands; they settled on them, made them their own, and set out again – east, north, and south.

The most amazing part – and one of humanity’s most fascinating human-adventure historical stories (mysteries?) – is how they crossed the Pacific from west to east in relatively simple (but actually quite swift) boats. Some evidence even suggests that they reached the west coast of South America and made contact with the then-locals – the Incas (the only inhabitants at the time).

And this epic emigration from what is today Taiwan to Rapa Nui (Easter Island) lasted about four thousand years!

So, if it took 2500 years to migrate the ~10,000 kilometers from what is today Papua New Guinea to Rapa Nui – that works out at about four kilometers per year on average. And so it went, by trial and error, venturing into the unknown and not always returning. It was a colossal migration – one of the greatest in human history!

// …And I keep returning to the story, since it’s just so fascinating )

How did they sail thousands of kilometers across the Pacific? Since I’m no expert, I’ll point curious readers to the wealth of resources available online. A good place to start would be here, or here, where you’ll find this here picture:

Though I recall seeing pictures of even larger ones, it was in boats like these that the Polynesians conquered the open seas. Scouts likely went first, and sometimes returned (though not always), bringing back news of islands and atolls. So what motivated them? Probably the usual mix: overpopulation, dwindling resources, social conflict, chronic hunger, and just plain curiosity.

By around 1200AD (the date most scholars agree on), Polynesians settled on Rapa Nui. And they must have reached other equally remote islands along the way – for example, what are today known as the Pitcairn Islands and also Ducie Island; but even from those, it’s still more than 1500 kilometers in a straight line to Rapa Nui! ->

Ok, so we’ve gotten an idea about the geography and how people arrived. Now, let’s discuss how they lived and what they got up to…

And, of course – when and why they erected the enormous moai statues:

Here’s what happened, apparently…

Archaeological studies show that when the Polynesians first arrived, the island was heavily forested, it was surrounded by ocean rich in fish, and the volcanic soil was quite fertile. The settlers enjoyed this abundance, and the island’s population grew. At its peak, roughly 15,000 souls may have lived here. Judging by the size and number of moai and other stone structures, they clearly had the resources for such large-scale projects. So life was comfortable and plentiful – at first.

But then, around 1500–1600, everything changed. Most importantly, the forests disappeared. An ecological disaster followed, resources became scarce, the population dropped to around 2000 or 3000, and moai chiseling ground to a halt. The latest statues date from this period.

So what happened? The most popular theory is anthropological: the island’s inhabitants “became their own worst enemies” and destroyed the forests for short-term needs. But other research suggests climate change and the introduction of rats (which ate tree seeds and saplings) played a role. But that the forest all disappeared sure is accurate; here, for example, is a lone clump of bamboo in the middle of the barren landscape:

By the time the first Europeans arrived, Rapa Nui was a treeless, hungry little island in the vast South Pacific:

Alas, worse was to come…

The Europeans arrived – bringing with them new epidemics. Then same Europeans began exporting the islanders as slaves for South America’s growing economies. In short: utter catastrophe. By the end of the nineteenth century, only 111 inhabitants were left. All the priests – the keepers of local culture and tradition – died out. And that was it. All that remained were mysterious stone statues, and petroglyphs with a still-undeciphered language.

Eventually, things improved: today, about 8000 people live on the island – roughly half of them identifying as indigenous. According to our guide, there are around a thousand inhabitants of “pure Rapa Nui” descent left.

And that’s all for today from Easter Island. More coming soon!…

The best hi-res photos from Easter Island are here.