October 6, 2025

A space-exploration museum like no other: oh my Gagarin!

Hi folks!

Since my tales from the Altai side are many and lengthy, today – an interlude in-between two of them for a breath of fresh air. Not that you can get air (or river water) fresher than that in Altai, but, I digress…

And so, just the other day, I finally managed to visit the RKK Energiya Museum in the town small city of Korolyóv (often spelled Korolev) just outside Moscow. The museum is dedicated to both the company’s own story and the history of the Soviet and Russian rocket-and-space industry as a whole. My impressions? Absolutely amazing! And with all due respect to the Museum of Cosmonautics, this place is better!

This is the very spot where all these technologies were invented and assembled, and – for those that returned from space – brought back to again. That’s what makes this place truly unique: the spacecraft you see here were typically produced in just two or three identical “copies”. One would fly into space, while the others stayed on Earth. So even if these specific pieces never made it to orbit, everything here is original – not mock-ups.

On the first floor: the descent modules – the real ones that carried Gagarin, Leonov, and Tereshkova. Oh yes – the actual modules! ->

By the way, even though the museum is inside a secure facility (belonging to the Energia Corporation), you can still visit if you send an advance request – which is just what we did.

Ok – let’s have a look around…

Ironically, it makes more sense to begin your tour on the second floor to follow the history in chronological order.

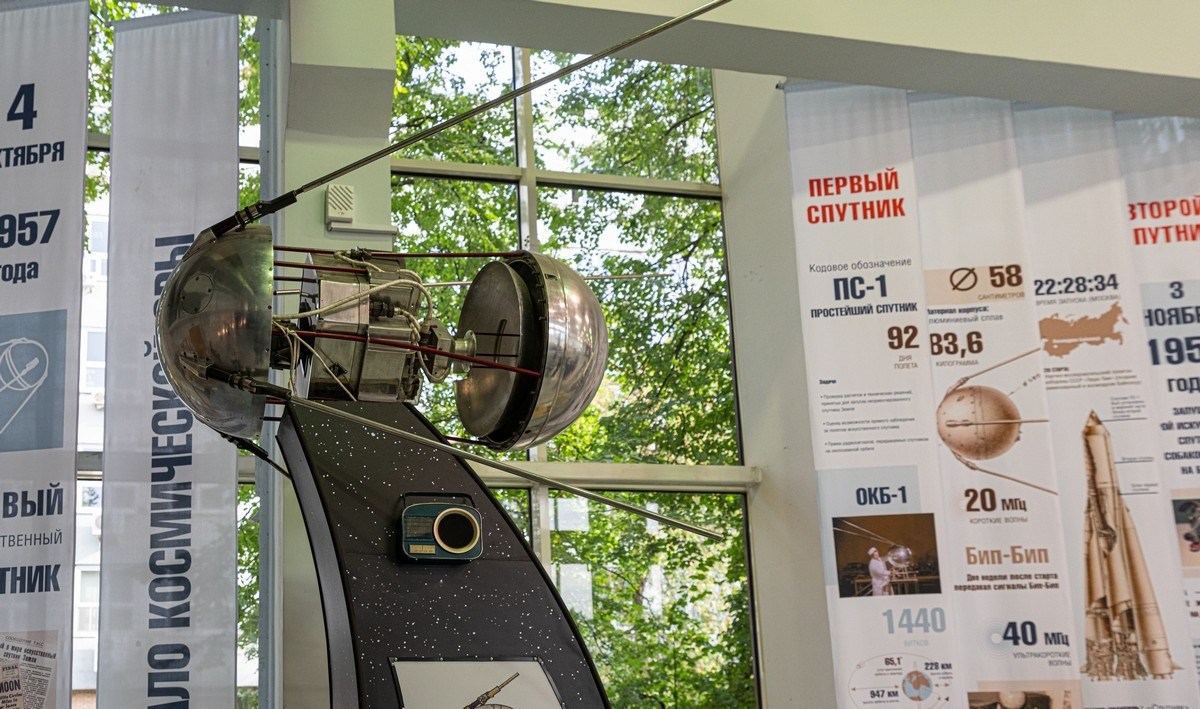

And so: on October 4 (my birthday, by the way), 1957 (eight years before I was born), the world’s first satellite was launched into space – Sputnik 1. // Btw: you might not know what sputnik in Russian means in English. Can you guess? It’s not too hard… Sputnik means satellite! There. Now you’re ready for the inevitable pub-quiz question one day )… And here it is:

Let me say it again: three identical copies of each spacecraft were produced. So even though this particular one never flew – it’s still an original. The one that did fly made global headlines with its legendary beep-beep-beeps, while the Russian word sputnik became international and entered foreign-language dictionaries as-is. Our heroic little device circled the Earth for 92 days, made 1440 orbits, and finally burned up in the atmosphere.

Sputnik 2 launched just a month later – on November 3, 1957 – and it didn’t go alone; it had a passenger inside: a dog named Laika! Sadly, there were no plans to bring her home; she was intended to be the first space sacrifice.

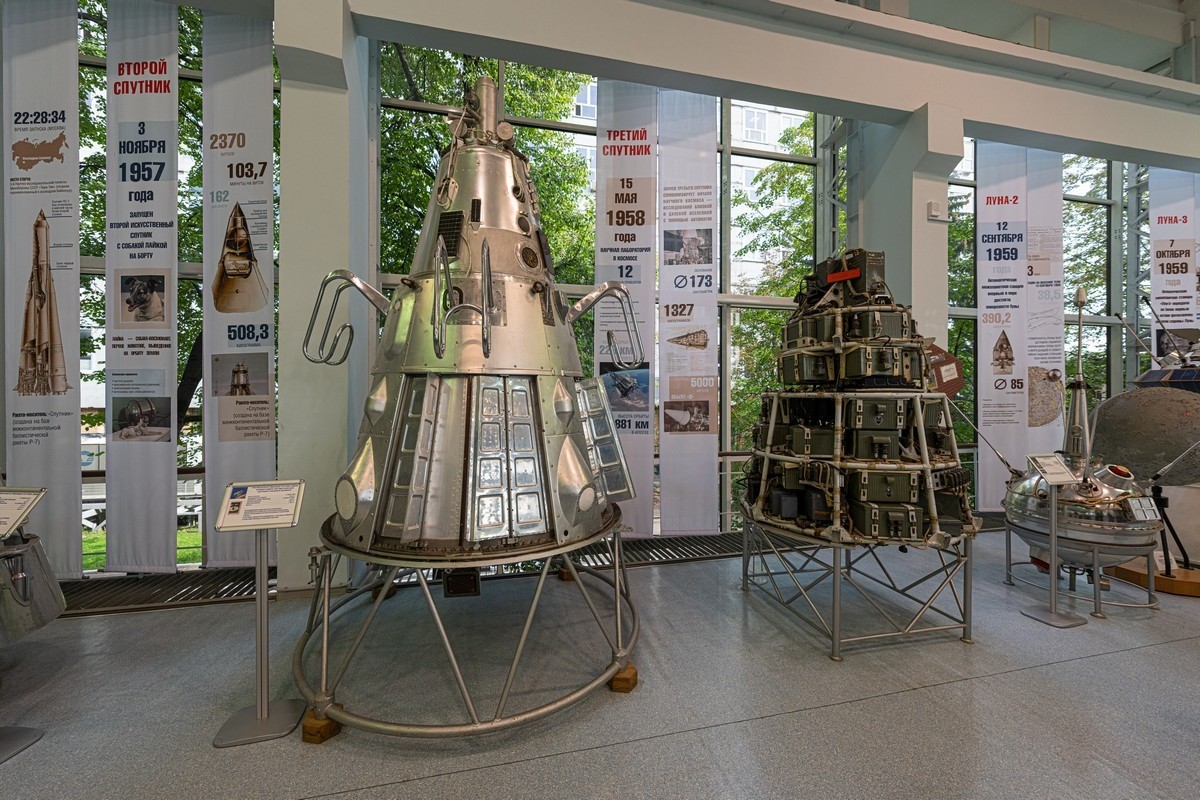

Sputnik 2 was a completely new design, and launched just a month after the very first flight! How fast did those Soviet engineers work? Did they even sleep? I won’t even ask about days off. If the space program had continued at that pace, we’d probably be taking weekend trips to the Moon by now. But things later slowed down…

The next successful launch was on May 15, 1958, with Sputnik 3 brimming with scientific equipment (there’d been an unsuccessful attempt before it). Sputnik 3 could receive commands from Earth and featured plenty of technical innovations. In the next photo, to the left is the satellite’s shell; to the right – its internal components. With modern technology, all that equipment would these days fit into something the size of an orange!

Next came the lunar missions – rather, the Luna missions (luna in Russian means moon in English). Luna-1 launched on January 2 (no nine-day New Year’s holidays back in the USSR back then!), 1959. The goal was to reach the Moon and… deliberately crash into it! Unfortunately, it missed due to a simple error. They say mission control back on Earth didn’t factor in the radio signals being delayed due to the great distance to the Moon. Or maybe the control systems were set up the day before – New Year’s Day – and, let’s say… due to the “fog” of the special holiday, those control systems weren’t set up quite correctly?!

Which is true? Maybe both. At any rate, the first spacecraft to break free of Earth’s gravity took important readings, but ended up flying past the Moon. Where is it now? Deep in outer space. And where are the other models of Luna 1 that didn’t go up into space? I don’t know – but they sure aren’t in this museum. Could that be because the mission was deemed a failure? I don’t know.

According to the internet, Luna 1’s trajectory was calculated and it became the first artificial satellite of the Sun – still circling in its own orbit and expected to return to Earth again in… 2109! Can’t wait!…

Oh, how quickly space technology developed back then (it truly was a “Space Race“). And it kept on doing so: six months later, on June 18, 1959, the Luna 2 mission launched… but failed. But by September that same year, the next mission succeeded. And still today, fragments of a spacecraft just like the one here rest on the Moon’s surface:

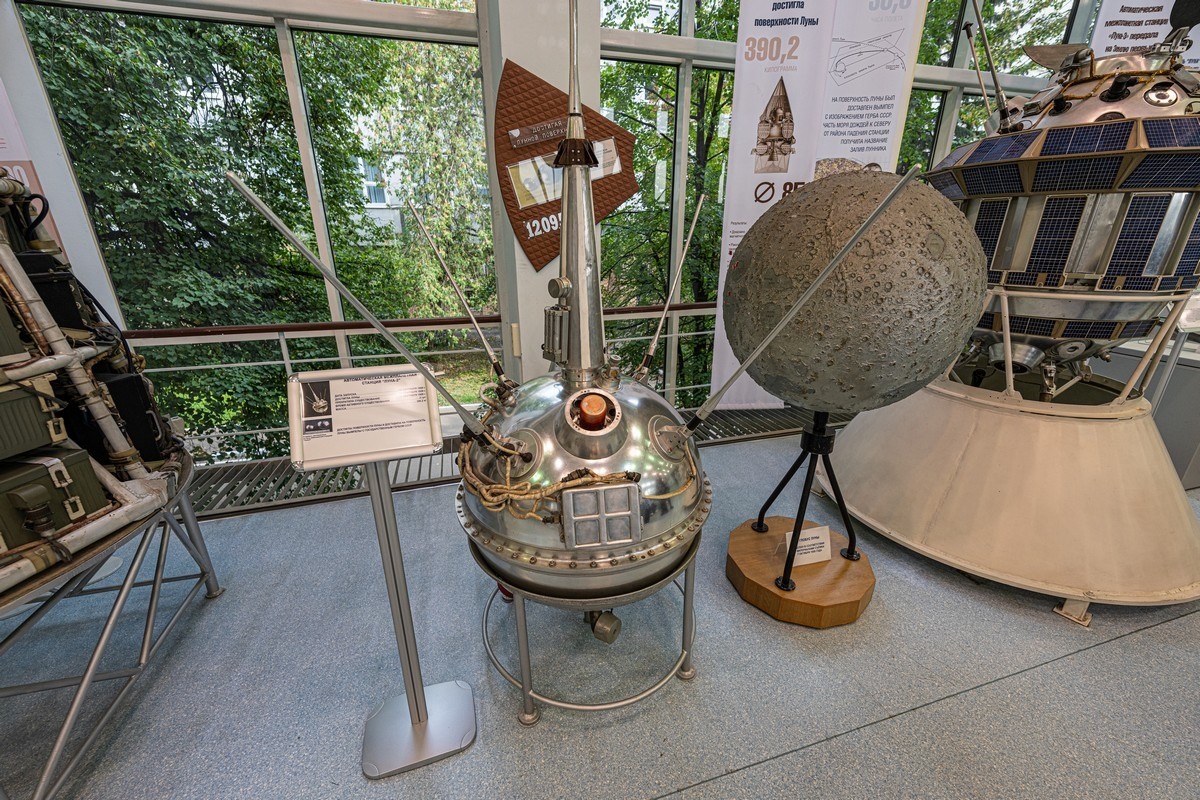

And once again on October 4 (my birthday) – but this time in 1959 (just two years after the first sputnik) – the Luna 3 probe was launched, which for the first time in history took photos of the dark side of the Moon. And here it is:

Taking and transmitting those images required some real advanced technical wizardry and chemical magic: the photos were automatically developed onboard, and then beamed back to Earth by a photo-TV system. Astounding.

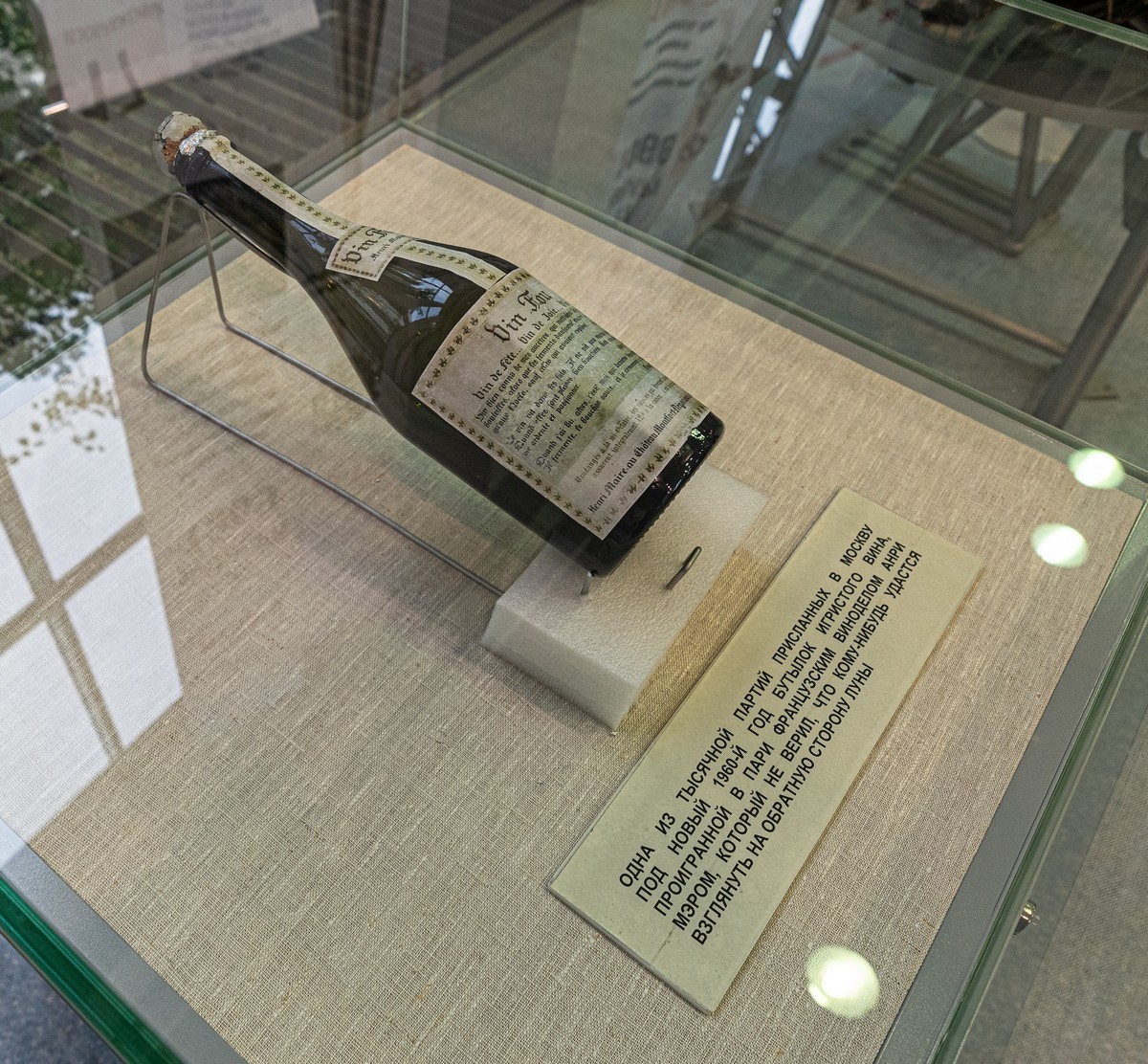

There’s a fun story connected with these photos. A famous French winemaker once made a bet with a Soviet diplomat – promising to supply a thousand bottles of his best champagne to anyone who could show him the Moon’s far side (accounts differ regarding the details). Anyway – when the images appeared in the press, he kept his word, and sent the champers… where he could: to the Soviet Academy of Sciences (no public contacts existed for the top-secret space program). Allegedly, some 300 bottles made it to the cosmonauts. Here’s one of them:

The next space-race goal: land a probe on the Moon. But a series of failures followed – some probes missed, others crashed. Not until Luna 9 did a probe finally make a soft landing on our nearest celestial neighbor – in 1966:

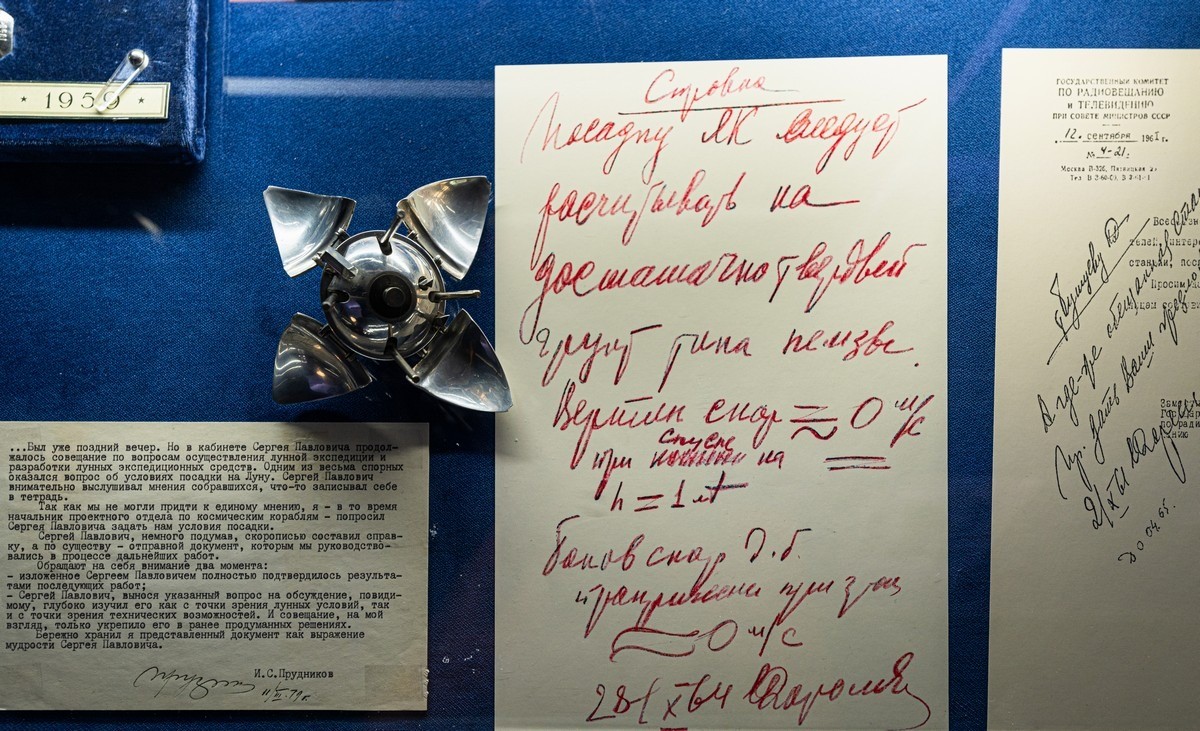

Here’s an interesting bit of trivia about this mission: scientists had disagreements regarding the Moon’s surface. Some thought it was solid; others insisted it was a deep, loose powder. In the end, Sergey Korolev ordered (!) everyone to assume the Moon’s surface as solid. There’s even a written order of his (it’s displayed elsewhere in the museum; more on that later).

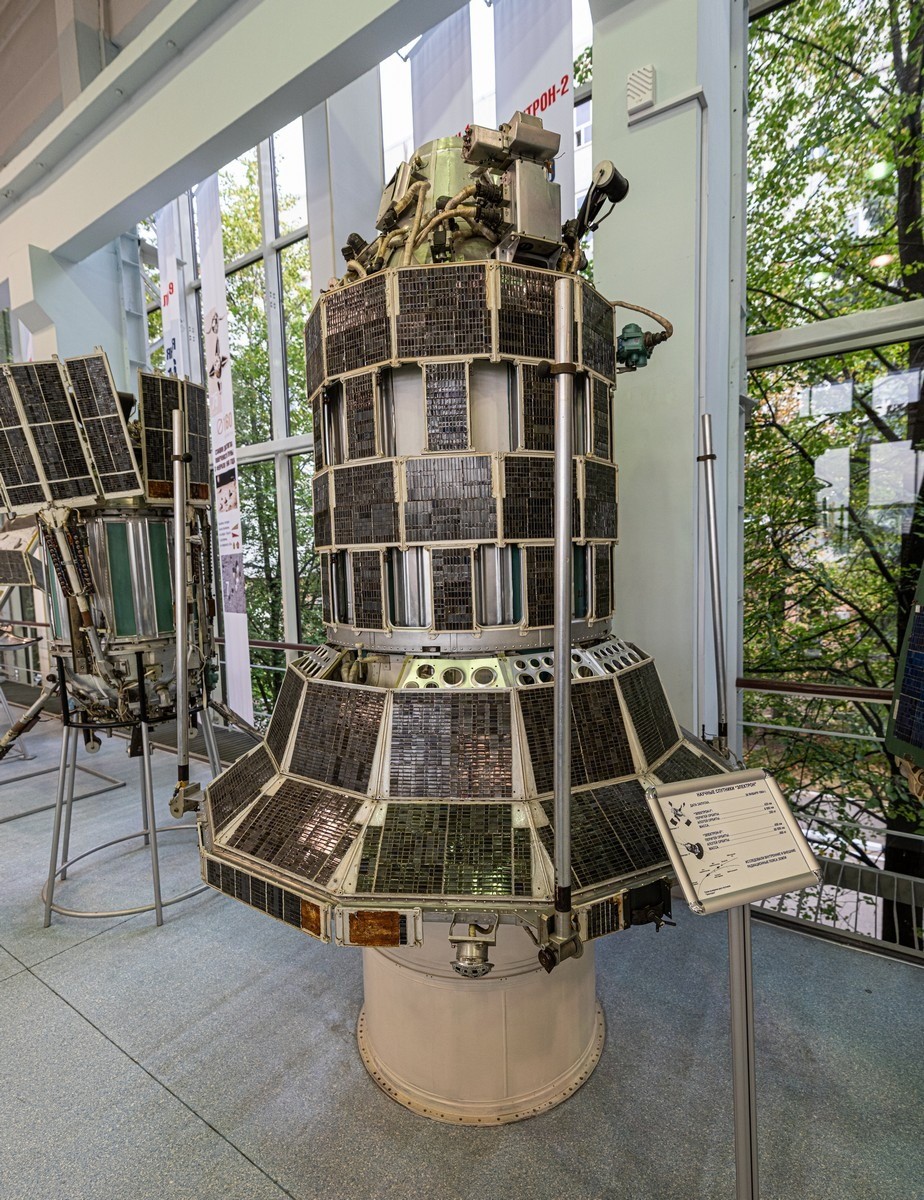

Then came the first satellites for more advanced space exploration:

The earliest communication satellites, which relayed TV signals from Moscow all the way to the Russian Far East:

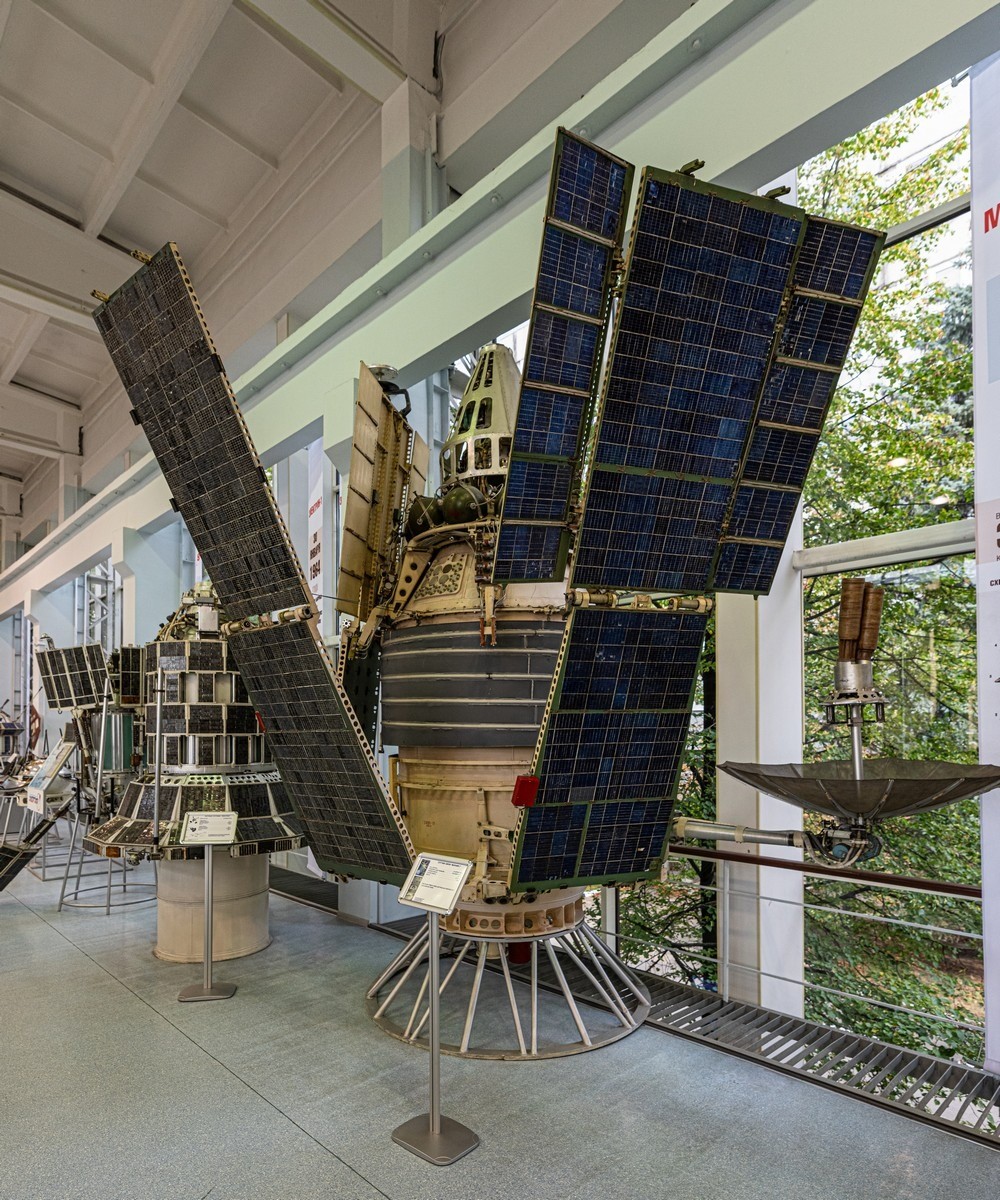

The Venera program for studying… which planet? Can you guess? Venera is the Russian for Venus! ->

An absolutely packed, fascinating exhibit!

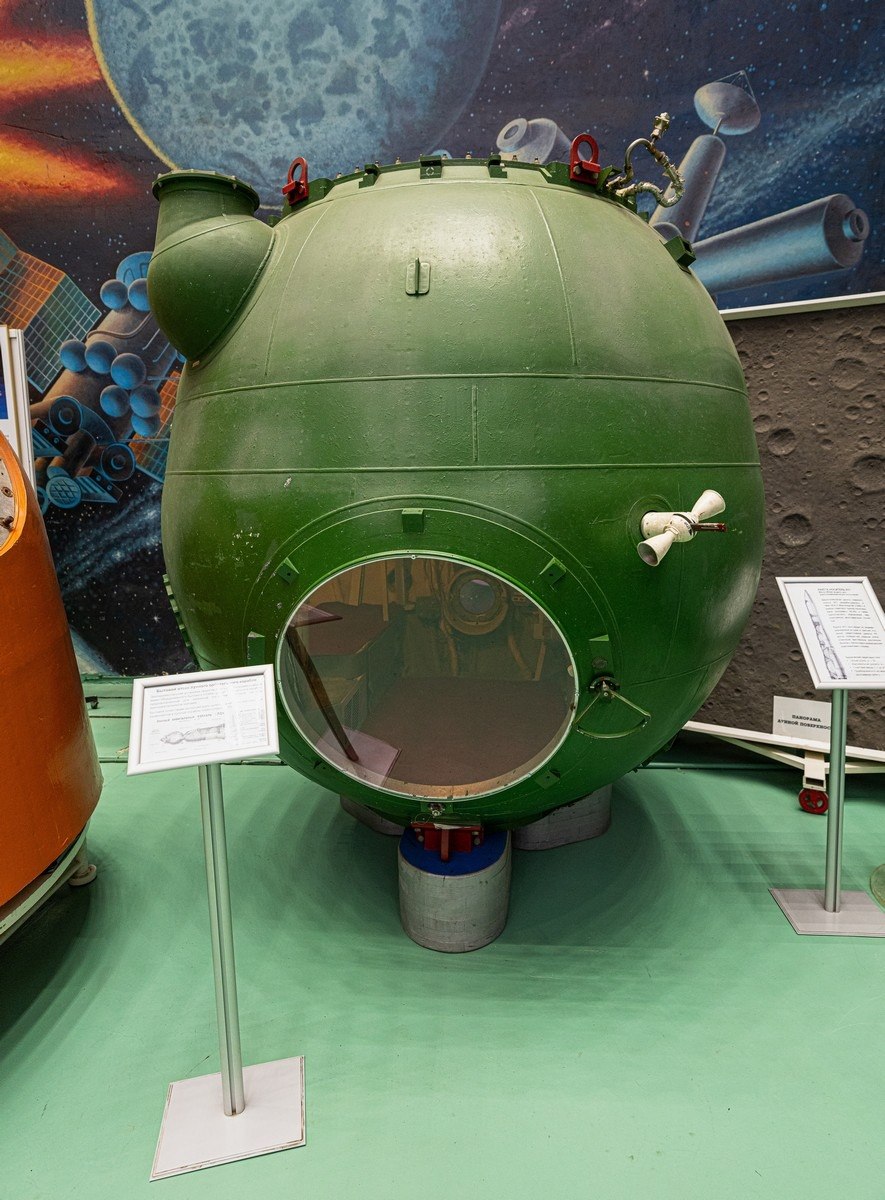

The first floor is just as engaging – dedicated to manned spaceflight. About half the floor is filled with spacecraft that actually flew in space and returned. This particular orb is the very capsule that Gagarin himself flew in!

But first, about… dogs! I was surprised (thanks, internet) to learn that dogs had been sent to high altitudes and even into space long before the era of human spaceflight. Dozens of dogs made these journeys; alas, not all survived. Some – like the above-mentioned Laika – were never meant to come back, so the museum’s focus is mostly on the descent modules from successful missions with the dogs alive and well:

Famous canine duo Belka and Strelka orbited the Earth and returned alive in August 1960:

After the dogs, it was time for humans:

On April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin launched into space to become the first human to do so aboard Vostok 1 – in this very capsule:

Yes, this is the one! And when the guide’s not watching, you can even give it a touch :)

Absolutely priceless. You can even peek inside the capsule:

What an exhibit! This capsule alone is worth the visit.

They also have the capsule of Tereshkova – the first woman in space – from her 1963 flight:

Here’s the ejection seat (to the right) that was inside:

And there’s Alexey Leonov – the first to perform a spacewalk, in 1965 ->

The Mir space station. As usual, three were made – one went into space, another is here, while the third is in Star City.

You can go inside Mir, look around, and see how cosmonauts (and later, astronaut guests) lived in orbit. In fact, there ended up being more Americans than Soviet or Russian cosmonauts on Mir!

The “bedroom” is vertical – because in zero gravity there is no “lying down” ) ->

All sorts of intriguing equipment, noisy fans, and a whole bunch of buttons – life in orbit is far from straightforward.

Rest room! (The Americans used diapers:) ->

Entrance to the science module:

It’s a shame that the floor is carpeted – interesting things are tucked away underneath, like a treadmill. You can see that in Star City. They even had a space shower and a sauna! Imagine the budgets for these space programs…

Next to Mir: Soyuz 19 – one half of Soyuz-Apollo (the Americans prefer it to be called Apollo-Soyuz for some reason:) – the docking of Soviet and American modules:

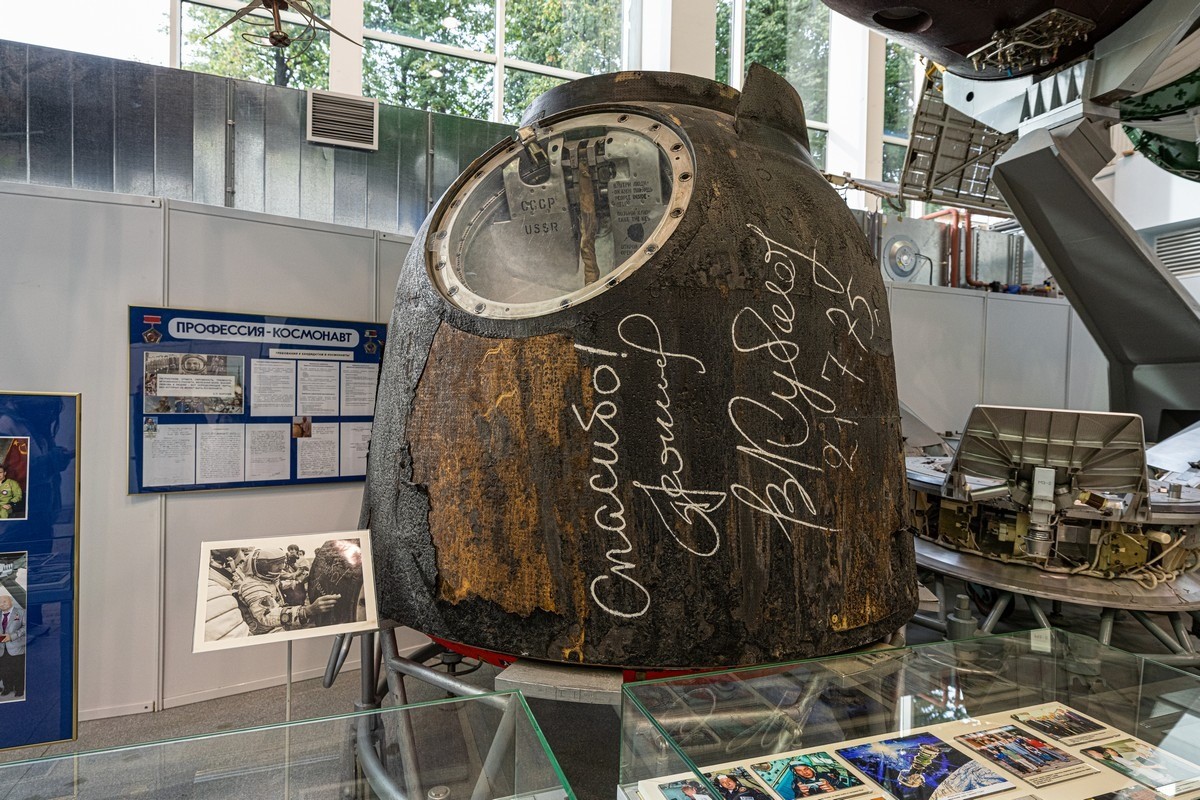

The descent capsule:

What an incredible place!

There’s another museum hall in the old assembly shop, about 300–400 meters from the first exhibit. It has even bigger items. For example, a Salyut space station (not sure which one):

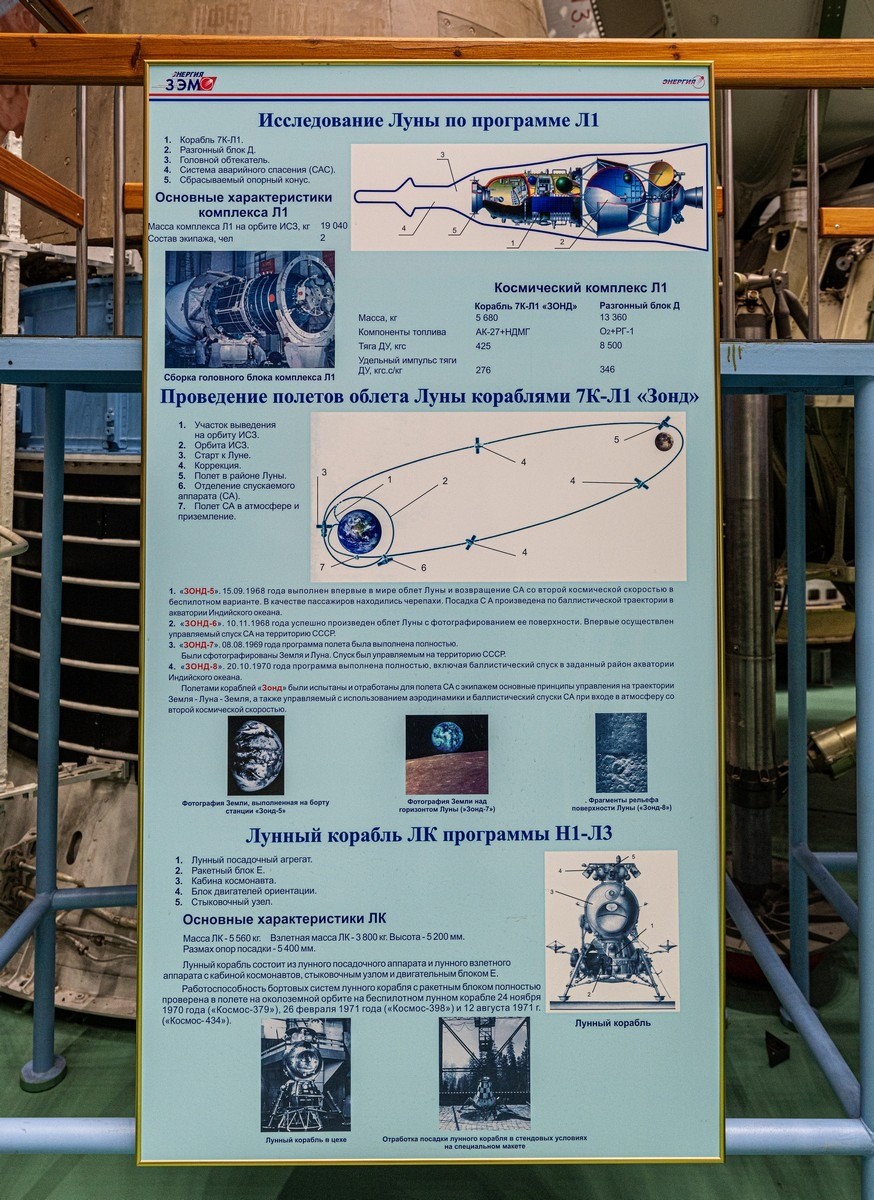

And all kinds of other objects: parts from the USSR’s unfinished lunar program, modules from Buran, and much more. It’s all a bit melancholy – the “lost era of firsts”. I hope it’s not lost forever…

Luna program items:

The living quarters section of the lunar ship:

So many grand plans…

And finally, the Sergey Korolev Museum – dedicated to the vision and energy of the man who made all of this happen.

His desk:

And the very note where he declared the Moon’s surface solid! ->

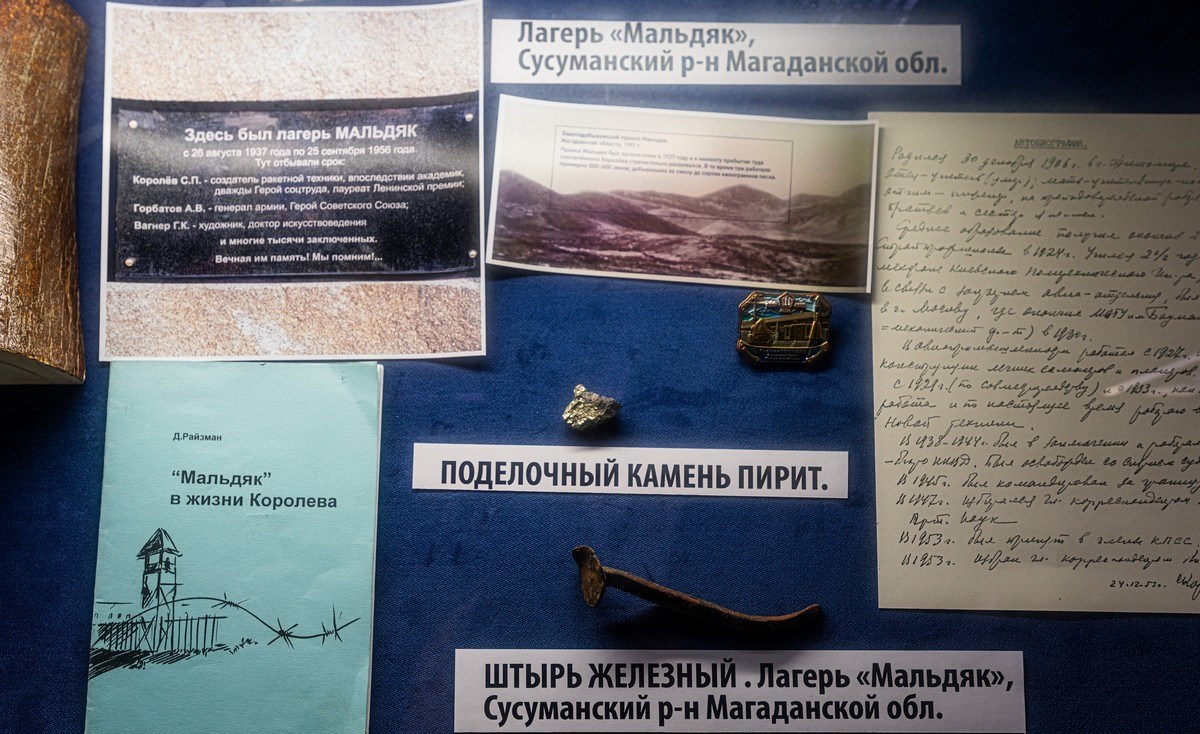

A chapter from his time in… the gulag – Susuman district, Magadan region, where he was involved in hard labor mining gold. Next time I’m in Susuman, I’ll remember that…

What a fascinating place.

Nearing the end of our excursion around the museums, I couldn’t help thinking how the later setbacks in the space program (with a few exceptions) likely boil down to two things: First, the shortsightedness of the country’s leadership, which slowed or underfunded the space program (or prioritized other things). Second, the sudden loss of the Chief Designer – with no worthy successor to continue this all-important (and endlessly fascinating) work with the same passion. And that doesn’t depend just on leadership or budget. There’s a lesson there.

The best, high-quality photos from the Energiya Museum are here.