July 23, 2020

An early-warning system for cyber-rangers (aka – Adaptive Anomaly Control).

Most probably, if you’re normally office-based, your office right now is still rather – or completely – empty, just like ours. At our HQ the only folks you’ll see are the occasional security guards, and the only noise you’ll hear is the hum of the cooling systems of our heavily-loaded servers given that everyone’s hooked up and working from home.

You’d never imagine that, unseen, our technologies, experts and products are working 24/7 protecting the cyberworld. But they are. But the bad guys are up to new nasty tricks at the same time. Just as well, then, that we have an early-warning system in our cyber-protection collection of tools. But I’ll get to that in a bit…

The role of an IT security guy or girl in some ways resembles that of a forest ranger: to catch the poachers (malware) and neutralize the threat they pose for the forest’s dwellers, first of all you need to find them. Of course, you could simply wait until a poacher’s rifle goes off and run toward where the sound came from, but that doesn’t exclude the possibility that you’ll be too late and that the only thing you’d be able to do is clear up the mess.

You could go full-paranoiac: placing sensors and video cameras all over the forest, but then you might find yourself reacting to any and every rustle that’s picked up (and soon losing sleep, then your mind). But when you realize that poachers have learned to hide really well – in fact, to not leave any trace at all of their presence – it then becomes clear that the most important aspect of security is the ability to separate suspicious events from regular, harmless ones.

Increasingly, today’s cyber-poachers are camouflaging themselves with the help of perfectly legitimate tools and operations.

A few examples: opening a document in Microsoft Office, a system administrator being granted remote access, the launch of a script in PowerShell, and the activation of a data encryption mechanism. Then there’s the new wave of so-called fileless malware, leaving literally zero traces on a hard drive, which seriously limits the effectiveness of traditional approaches to protection.

Examples: (i) the Platinum threat actor used fileless technologies to penetrate computers of diplomatic organizations; and (ii) office documents with malicious payload were used for infections via phishing in the operations of the DarkUniverse APT; and there are plenty more. One more example: the fileless ransomware-encryptor ‘Mailto’ (aka Netwalker), which uses a PowerShell script for loading malicious code directly into the memory of trusted system processes.

Now, if traditional protection isn’t up to the task, it’s possible to try and forbid to users a whole range of operations, and to introduce tough policies on access and usage of software. However, given this, both the users and the bad guys will eventually probably find ways round the prohibitions (just like the prohibition of alcohol was always gotten around too:).

Much better would be to find a solution that can detect anomalies in standard processes and for the system administrator to be informed about them. But what is crucial is for such a solution to be able to learn how to automatically determine accurately the degree of ‘suspiciousness’ of processes in all their great variety, so as not to torment the system administrator with constant cries of ‘wolf!’

Well – you’ve guessed it! – we have such a solution: Adaptive Anomaly Control, a service built upon three main components – rules, statistics and exceptions.

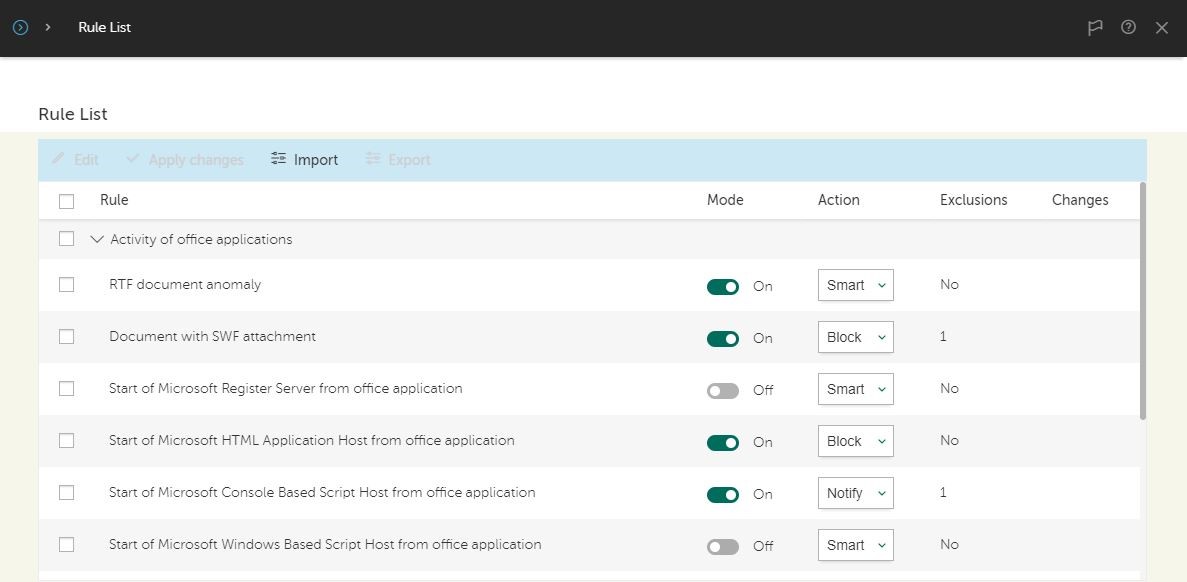

Rules cover the main office applications, Windows Management Instrumentation, standard scripts and other components, together with a list of ‘anomalous’ activity. These rules are a part of the solution and don’t require the administrator to create them again.

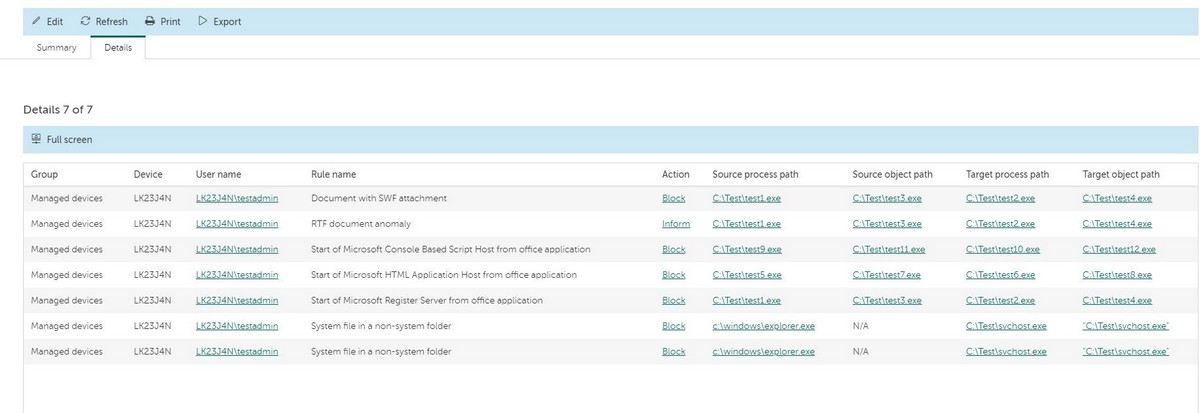

After activation, for around two weeks the system studies the processes that take place habitually at an organization, detects deviations from standard rules (i.e., gleans statistics), and creates a ‘personalized’ list of exceptions. This study period can be complemented by, for example, the system administrator creating his/her own exceptions for some specific process, or by finding an unforeseen anomaly. And the study process can even split up into departments so that, for example, finance folks can’t launch Java scripts, while R&D folks can’t get access to financial tools.

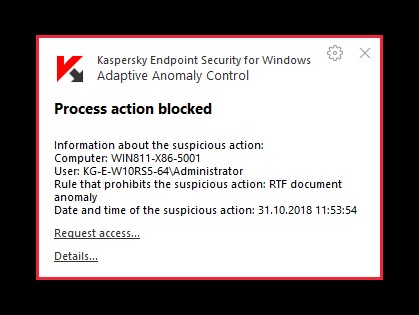

The system flags any deviations from the list of exceptions, indicating both the particular suspicious process and device on which it’s launched. For example, the launch of Windows Command Processor or HTML Application host by a PowerShell script from an office application or a virtual machine is technically possible, but it’s hardly a permitted operation. Or let’s say that if a file with a typical name for a system file is saved in a folder that’s not a system folder – that would be a signal to take a real close look at the application.

Additionally, the system administrator can block a process, or permit it but with the user being informed about it. Also, on request, the observation period for certain rules can be increased so as to study more closely how they’ll be applied in the future.

“So why’s endpoint protection needed at all if the system works so well?” asks the skeptically-minded forest ranger system administrator. Because Adaptive Anomaly Control should be viewed as an early-warning system, merely indicating where suspicious activity is taking place. Actually fighting the threat – that’s the task of other key protection components, like EDR-solutions.

And that’s your basic introduction to Adaptive Anomaly Control, folks!

PS: And I didn’t use the forest ranger comparison accidentally, for forests (and wild countryside) are at the forefront of my mind at the mo: I need to start packing for my summer expedition around wild locations of Altai. Individual protection and early-warning systems are just the kinds of things I’ll be needing!…