June 15, 2014

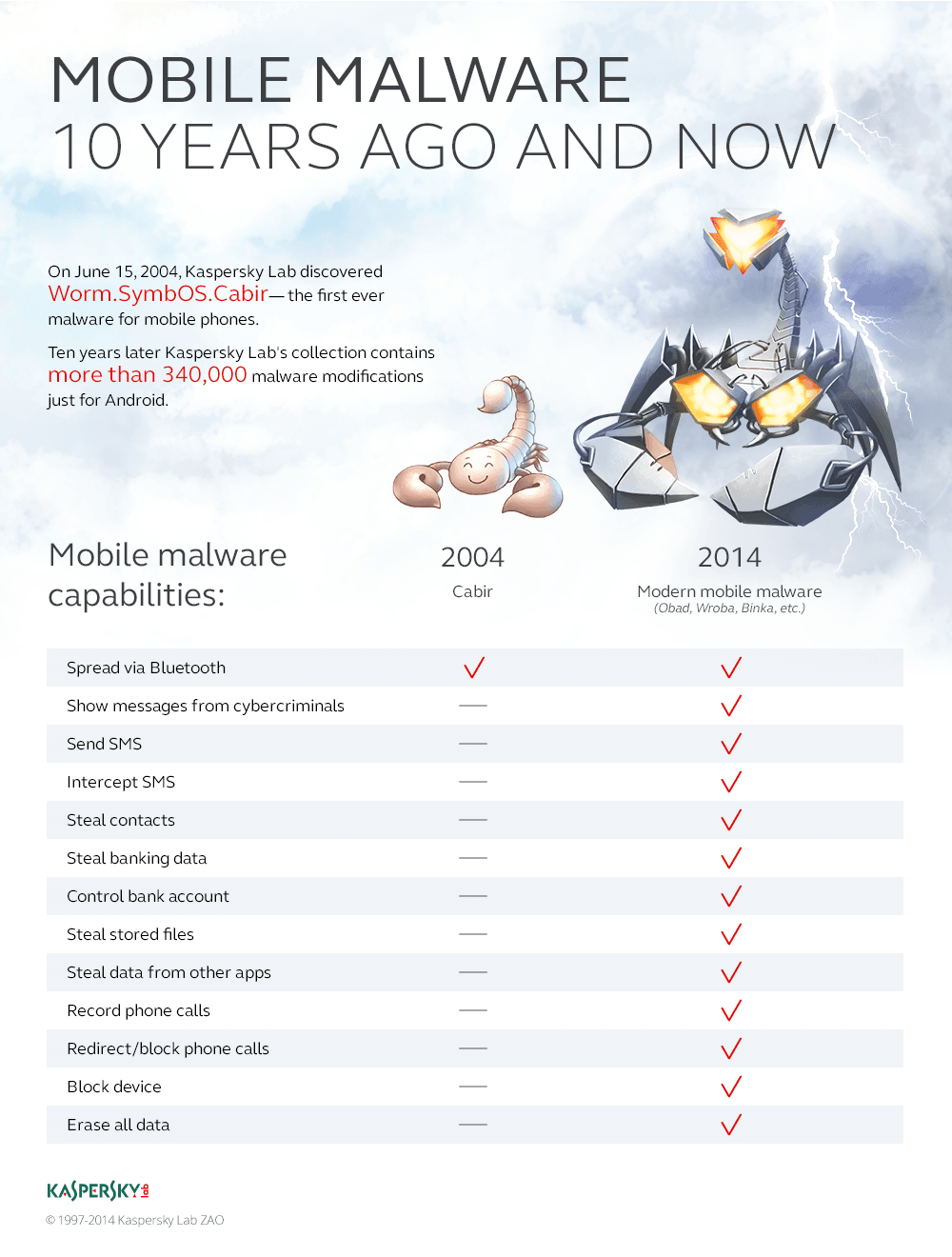

10 years since the first smartphone malware – to the day.

On June 15, 2004, at precisely 19:17 Moscow time something happened that started a new era in computer security. We discovered the first malware created for smartphones.

It was Cabir, which was infecting Symbian-powered Nokia devices by spreading via unsecured Bluetooth connections. With its discovery the world learned that there was now malware not just for computers – which everyone already knew too well about (save for the odd hermit or monk) – but also for smartphones. Yes, many were scratching their heads at first – “viruses infecting my phone? Yeah, pull the other leg” – but the simple truth of the matter did finally sink in sooner (= months) or later (= years a decade!) for most people (some still aren’t aware). Meantime, our analysts made it into the history books!

Why did we christen this malware Cabir? Why was a special screened secure room created at our Moscow HQ? And how did Cabir end up in the pocket of an F-Secure employee? These and other questions were recently put to Aleks Gostev, our chief security expert, in a interview for our Intranet, which I thought I’d share with you here; might as well have it from the horse’s woodpecker’s mouth…

Incidentally, the story started really running when we used these two devices to analyze the malware:

…but more about those below…

– The Cabir virus first appeared 10 years ago. Back then what was the overall situation with mobile malware?

Mobile viruses were almost non-existent 10 years ago. This is how I remember things from back then: in early 2004 we were holding an international press conference, and one of the journalists asked me when the first virus for cellphones would appear. I replied by next year’s conference – for certain. Sure enough, some months later – it appeared…

One of our shift virus analysts was sent an unusual file, whose platform it was supposed to operate on was unknown. So he asked his colleague, Roman Kuzmenko, for help with the analysis of the suspicious object. Roma was the natural choice, incidentally, being as he is very much a wunder-analyst and unparalleled in unlocking the mysteries of the oddest of things. As could have been expected, it only took him a couple of hours to work out that what we had here was a virus for the Symbian OS running on an ARM processor. And this duo existed only on cellphones – specifically, on Nokia ones.

At that time, our experts couldn’t immediately understand what the virus actually did, so we had to start running tests. But first we needed to get hold of a Nokia smartphone, which proved no easy task! Such ‘advanced’ phones were not quite as common as they are today :). In the meantime our anti-malware lab continued to analyze the virus, and soon they found… the bomb! They worked out that its key features were the ability to command the Bluetooth protocol and transfer files. It looked like an absurdly efficient means of spreading disease – virus-based disease…

– Returning to the lack of Nokias in possession, does that mean to say that back then you didn’t have the equipment for testing malware for mobile devices?

It does. We didn’t have a selection of all the smartphones in operation back then for quick testing, as the idea of needing such a collection naturally hadn’t occurred to us yet – cellphone viruses still didn’t exist.

What our analysts had successfully analyzed here (which was later named Cabir – see below) was the first virus for cellphones, and it became a kind of a starting gun – signaling the start of the race for virus writers to create malicious code for smartphones – and create it is indeed what they did, with alarming speed. So much so that by the end of the year it was clear that we really needed a new department to analyze exclusively mobile viruses, especially since they were found to be quite different to computer viruses.

So we founded such a department, with me heading it. Later I was joined by another analyst, Denis Maslennikov, and one of the first things we decided together was to purchase all the mobile devices that existed on the market that could be attacked by malicious code – even if just theoretically. This was quite fun. After all, who doesn’t like buying new kit – never mind loads of it in one go? We procured all the Symbian devices there were, plus all the phones based on Windows, BlackBerry, and so on. Still to this day, we continue to add new mobile devices to our exotic and very complete collection – in case a new mobile threat appears and we need devices to test with sharpish.

– So why is it named Cabir? After all, the screenshots on Securelist show that the file contains a different name.

Oh, that’s a whole other story! The screenshot shows the name the author gave it – Caribe. However, it’s customary in the antivirus industry to name viruses not according to how their authors’ named them, but to come up with new names – so as not to fuel the authors’ egos… oh, and maybe stamp our authority all over the conquered viruses!

So there we were doing really advanced analysis work – deciding on a name – when our colleague Elena Kabirova walked into the room. Given the Jungian weirdness of the coincidence of her surname being similar to the virus’s name, we asked her if she’d like her name to go down in history as the name of the very first virus for cellphones. Well, the rest… is history :).

– So how did you manage to unlock the identity of the virus without actually having one of the targeted phones?

As often happens with viruses, we received an email with nothing but an attachment – which contained the virus file. It was sent to our address created specifically for this – newvirus@kaspersky.com. We knew about the sender of the email – he was listed in our databases as… not exactly a virus writer, but someone ‘associated with’ the underground. Once in a while he would send us new malware samples created by European virus writers. As a rule, everything he’d send always turned out to be something serious, i.e., new and unique, so we knew this one would be something significant too straight away. Sure enough, this was soon confirmed by strings contained in the malware code (including mention of 29A). It was then clear that what we had here was a malicious program authored by the notorious, long-established international group of virus writers called 29A.

At the time, we didn’t know that the sender of the email had simultaneously sent the virus to several other antivirus companies; still, that didn’t really matter: we were the only ones able to figure out what the file was all about :).

– So what happened next?

After initial analysis of the virus it became clear that for testing we’d need not one but two smartphones running Symbian, because the virus transmitted itself from one phone to another using Bluetooth. So we copied the virus onto the first phone, started Bluetooth on the second in Discoverable Mode – and in an instant a request to accept the file came up on the second phone. And after receiving and running the file, the second phone automatically started searching for all available Bluetooth-enabled devices nearby. Thus, we confirmed that the virus disseminated and propagated via Bluetooth. Next, we distributed a press release telling the world about the appearance of the first cellphone virus. But that was only just the beginning…

The functionality of the virus and its subsequent modifications presented us with a big practical problem at our office. After all, we were not in a vacuum, but in a typical working environment, where all around could have been folks who could accept this file on their Nokias. We realized we were putting our own colleagues in jeopardy with possible infection! This prompted us to fit out a special room with iron shielding where we could experiment safely with mobile malware.

Inside the room there was zero mobile coverage, and any and all communications were jammed: everything was done to prevent viruses from spreading beyond the room. The room turned out to be not only a necessary tool for testing mobile viruses, but also a favorite attraction for media folks, so we always took them there to have a look. These days the mobile malware scene has changed dramatically, and old school viruses like Cabir have ceased to exist, so there’s no need for such a room anymore, much to the disappointment of media types :).

– You said this malware was created by a certain group of virus writers. Tell me more about it.

It was the most legendary group of virus writers in history. They created a massive amount of advanced and unique things. The group consisted of virus writers from all around the world, with membership changing all the time, but there was always a sort of a main skeleton crew made up of people from Spain and Brazil. One of them, a man named, if my memory serves me well, Vallez, created Cabir. The 29A group were not cybercriminals by modern standards – they were virus writers creating malware to test and demonstrate new virus technologies. Thus, they were motivated by ideology rather than personal gain. They were firsts in many respects: the first to create a macro virus, the first to create a virus for the Windows 64 platform… Each creation of 29A was a breakthrough, used afterwards by other virus writers, and then by cybercriminals. And we have to remember that at that time – in 2004 – cybercrime was only just beginning to emerge. Back then the majority of virus programs tended to be created just for kicks, by people trying to… ‘express themselves’.

The group that created #Cabir was known for its sophistication and its own e-zineTweet

The group existed until around 2009, though before then it had become a lot less active. Some members of the group were arrested – in Spain, Brazil, and the Czech Republic – while others continue to write malware. We know this because we still come across familiar bits of code – kind of like their personal handwriting or thumbprint.

– You mentioned later modifications of Cabir. How did Cabir develop?

The group that created Cabir was known not only for its sophistication, but also for the fact that it issued its own e-zine. And a few months after the first appearance of Cabir, it published information about the worm together with snippets of executable code, so some time later new modifications of Cabir began to appear – every week. There was one virus writer with an extremely strong desire for fame who persistently sent us modifications of the virus with a request to give it a separate name! He kept returning, again and again – for a year! – trying to somehow get into the history books of mobile viruses. In the end he got what he wanted: we indeed classified one of the modifications as a separate family; we kinda had to.

– Why is F-Secure somehow closely associated with the Cabir virus?

Cabir managed to cause a minor, but rather curious and thus well-publicized outbreak. It just so happened that in 2005 a certain athletics tournament was taking place in Finland. Which meant there was a stadium crammed with folks from all over the planet. Now, the damage radius of Cabir was generally very small – as Bluetooth’s range is only about 20 meters. However, here, in a packed stadium?… :). The problem was made even worse by the fact that Nokia phones come from Finland and are thus extremely popular there! Needless to say, Cabir easily got into the stadium – on a cellphone in a pocket of one of the tens of thousands of spectators.

So all the time while the athletes were running on the track, simultaneously the Cabir virus was running too – all around the stands. I know, you couldn’t make this up! Anyway, eventually Cabir was Bluetoothed into the cellphone in a pocket of an F-Secure employee at the stadium (question – why was he accepting unknown files by Bluetooth?:). Days later the Finnish antivirus company opportunely offered to install in the stadium a Bluetooth scanner giving visitors the chance to check whether their phones had been infected with the virus. So there’s your link – read: gimmick :) – between Cabir and F-Secure.

– What did this mobile virus do, besides Bluetooth breeding?

– If you’re referring to direct financial losses, it didn’t cause any. It exhausted the battery pretty quickly – in just two to three hours – because constantly searching for Bluetooth connections places a heavy load on the battery. In monetary terms, the later mobile viruses that in addition to transmitting themselves sent MMSs to premium-rate numbers were far more damaging. For example, a well-known virus post-Cabir, Comwario, caused an epidemic in a Spanish city whose financial damage came to the tune of several million euros.

– Today we’ve talked about a particular mobile threat – how it spread and the group behind it. But what we haven’t discussed is the issue of protecting mobile platforms back then. Did we really have nothing to respond with?

– Well, things weren’t so bad, because even before the discovery of Cabir viruses for Palm OS (for Palm PDAs) had appeared, so many antivirus companies had already developed protection for that platform. But eventually passions subsided, new viruses didn’t appear, and many people just stopped thinking about Palm OS viruses and protection against them. (Also, Palms weren’t smartphones, and weren’t all that popular – compared with hugely popular cellphones.) But with the discovery of Cabir, we called up again all we had learned earlier, modified it, and shortly after had on the market an antivirus for mobile platforms. Ever since, more and more mobile viruses have appeared. And ever since, we’ve been modifying and updating our mobile protection too. Nothing to respond with, you ask? Hardly!