October 28, 2016

The Internet of Harmful Things.

In the early 2000s I’d get up on stage and prophesize about the cyber-landscape of the future, much as I still do today. Back then I warned that, one day, your fridge will send spam to your microwave, and together they’d DDoS the coffeemaker. No, really.

The audience would raise eyebrows, chuckle, clap, and sometimes follow up with an article on such ‘mad professor’-type utterances. But overall my ‘Cassandra-ism’ was taken as little more than a joke, since the more pressing cyberthreats of the times were deemed worth worrying about more. So much for the ‘mad professor’…

…Just open today’s papers.

Any house these days – no matter how old – can have plenty of ‘smart’ devices in it. Some have just a few (phones, TVs…), others have loads – including IP-cameras, refrigerators, microwave ovens, coffee makers, thermostats, irons, washing machines, tumble dryers, fitness bracelets, and more. Some houses are even being designed these days with smart devices already included in the specs. And all these smart devices connect to the house’s Wi-Fi to help make up the gigantic, autonomous – and very vulnerable – Internet of Things, whose size already outweighs the Traditional Internet which we’ve known so well since the early 90s.

Connecting everything and the kitchen sink to the Internet is done for a reason, of course. Being able to control all your electronic household kit remotely via your smartphone can be convenient (to some folks:). It’s also rather trendy. However, just how this Internet of Things has developed has meant my Cassandra-ism has become a reality.

A few fresh facts:

Last Friday more than 80 large websites – including Twitter, Amazon, PayPal and Netflix – were either down or working intermittently. It turned out that the cause was a DDoS attack against the company Dyn, which provides the affected sites with DNS services. You may think ‘ah, DDoS attack – these things happen occasionally on the Internet’. Thing is, after digging deeper, it turned out that Dyn was attacked by the Mirai botnet – made up of… IP-enabled cameras, DVRs and other connected bits of IoT kit.

Mirai turned out to be rather simple malware, which scans the Internet for IoT devices, connects to them using default logins and passwords, secures admin rights, and carries out the commands of the hackers. And since it’s rare that a user changes the default login and password on such devices, recruiting several hundred thousand zombies for the botnet was pretty straightforward.

So, a simple botnet created by amateurs and made up of all sorts of smart devices was able to severely disrupt some of the largest Internet sites in the world for a time. The botnet has shown up before: in the most powerful DDoS attack ever known, which targeted Brian Krebs’ blog (with a peak power reaching 665 Gbps).

I reckon that in the near future a lot of popcorn – or antidepressants – will come in handy…

Mirai’s size is estimated to be of around 550,000 bots, while the whole of the IoT is thought to be made up of somewhere between seven and 19 billion devices (in five years it’s expected to go up to 50 billion). So, how many of those are vulnerable? How many can be recruited for hacker attacks? That’s a tricky one to answer, but one thing for sure is that Mirai has lots and LOTS of potential for causing lots and LOTS of bother. Especially since the source code of the malware has been published on the cyber-underground forums, meaning the techniques are openly available to just anyone who might have an interest in this – and that includes the mass of amateurs with Herostratic delusions of grandeur.

The owners of infected IoT devices wouldn’t have noticed that their kit took part in the attack, just the same as, right this minute, you won’t know if your IP-camera is being used for a DDoS attack on this or that respected net resource. And users will hardly be motivated by the unnoticeable jump in outgoing traffic to get some basic protection for their gadgets (as basic as a new login and password). However, there are other cyberthreats that are far less benign which can turn a smart home into an awful nightmare while emptying the contents of its owner’s wallet.

The Phantom Menace

I won’t take it upon myself to estimate how many billions of dollars cyber-extortionists have made in recent years – besides ‘many’. Despite the concerted actions of various law enforcement bodies and the IT security industry, an epidemic of cryptors and lockers has spread across the Internet so… epidemically, that an active user not having been attacked and not knowing anyone personally who has been attacked is practically unheard of.

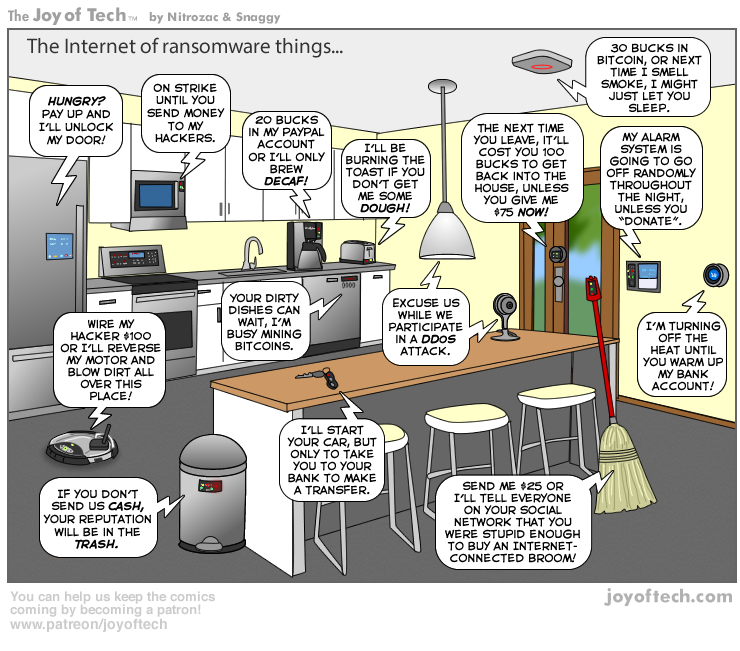

The ransomware business is doing great, but every business on the planet always wants to do better. Enter billions of vulnerable IoT devices – right on cue. Sadly, the owners of smart fridges and tumble dryers think their kit is of no interest to the cyber-baddies. Well, in a way, they’re right: the cybercriminals aren’t interested in fridges and tumble dryers – but they’d be very interested in receiving a ransom for them. See where we’re headed?…

… We’re headed here, for example (a thermostat):

Your front door won’t open? The heating’s shut down in the dead of winter? The coffee machine won’t stop emitting espresso, no matter what you do? The TV’s gone all Poltergeist? The Hoover’s doing the fandango? Alas, these hacking examples aren’t science fiction; they could easily occur in reality.

As often happens with new markets, in the race for better functionality, IoT manufacturers have neglected security.

Yes, of course, we’re here and ready to help with specialized expertise and ready-made solutions (yep – our test lab will start looking like a home appliances store). But we only get told post-incident, so can only come to the rescue later after something’s gone wrong: we’re not consulted at the design stage as security isn’t deemed important, and users don’t get a handle on the how real the threats really are.

It’s not for nothing that smart devices are often referred to as ‘smart’ devices – i.e., with the inverted commas. After all, the brains of these devices fit into a tiny bit of memory on a cellphone. Manufacturers have a long way to go until smart devices can be written without the ”. And it’s hard to tell now how much time will be needed to go ‘real’ smart; therefore, ‘saving of the world’ and its wallets is entirely in our hands. Accordingly, I suggest that you, dear reader, right now get to work on providing at least basic security for all your IoT kit, including routers, printers and everything else:

First: Change the logins and passwords, even if they’re already not the default ones.

Second: Install the latest patches from the manufacturers’ sites.

Third: Put a reminder in your phone or organizer for every three months to do the above two things.

Brian Krebs and in fact the whole of the Internet will be grateful to you, plus you will never see anything like the following:

What could be the next threat to the Internet of Things? @e_kaspersky explains IoT-targeted #ransomwareTweet